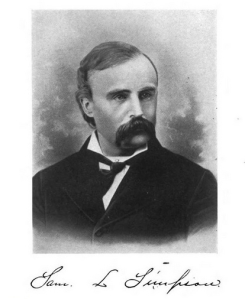

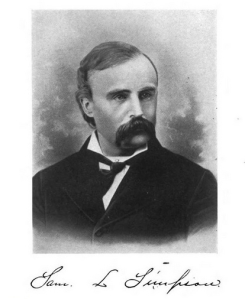

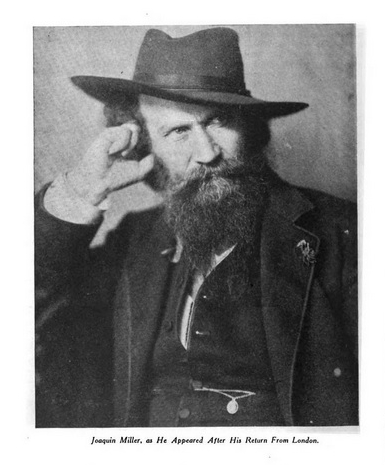

Samuel Leonidas Simpson, the “Burns of Oregon,” is widely regarded as nineteenth century Oregon’s most beloved poet. A prolific writer whose poems and stories were published throughout the Pacific Northwest, Simpson is remembered today for only one poem, “Beautiful Willamette,” written when he was twenty-two years old. At the height of his fame, however, Simpson’s various talents were praised extensively by an adulating press. The following editorial from the Oregon State Journal, Eugene, is but one example: “Some of our contemporaries express the opinion, in which we freely concur, that Sam L. Simpson is the most brilliant literary genius in Oregon.” (November 7, 1874) Even after Simpson’s death, the adulation continued. One month after his passing, the editor of the Salem Daily Journal remarked: “[Simpson] will stand in literature as the greatest writer our state has produced.” (July 11, 1899) The editor of the Oregonian was even more blunt: “The death of Sam L. Simpson leaves an absolute blank in respect of the fact that we have among us no poet of merit or reputation.” (July 18, 1899) This pronouncement was made in spite of the fact that at the time, several prominent Oregon poets were still living, including Joaquin Miller, Belle W. Cooke, Frances Fuller Victor, and Ella Higginson.

Samuel Leonidas Simpson, the “Burns of Oregon,” is widely regarded as nineteenth century Oregon’s most beloved poet. A prolific writer whose poems and stories were published throughout the Pacific Northwest, Simpson is remembered today for only one poem, “Beautiful Willamette,” written when he was twenty-two years old. At the height of his fame, however, Simpson’s various talents were praised extensively by an adulating press. The following editorial from the Oregon State Journal, Eugene, is but one example: “Some of our contemporaries express the opinion, in which we freely concur, that Sam L. Simpson is the most brilliant literary genius in Oregon.” (November 7, 1874) Even after Simpson’s death, the adulation continued. One month after his passing, the editor of the Salem Daily Journal remarked: “[Simpson] will stand in literature as the greatest writer our state has produced.” (July 11, 1899) The editor of the Oregonian was even more blunt: “The death of Sam L. Simpson leaves an absolute blank in respect of the fact that we have among us no poet of merit or reputation.” (July 18, 1899) This pronouncement was made in spite of the fact that at the time, several prominent Oregon poets were still living, including Joaquin Miller, Belle W. Cooke, Frances Fuller Victor, and Ella Higginson.

Since his death, several writers, including literary historians John Horner and Alfred Powers, have numbered Simpson among the major literary figures of nineteenth century Oregon, and it is therefore surprising to discover very little has actually been written about his life. “It has been singularly difficult to find exact information about him,” bemoaned Powers in History of Oregon Literature. “The few brief biographical accounts of him are vague and conflicting in their facts, being unfortunately consistent only in giving the year of his death as 1900 instead of correctly as 1899.” (Powers, 295-96)

Powers’s book, published in 1935, and the chapter on Simpson included therein, did little to revive interest in the dead poet. Over the past century this brief biographical sketch has been one of the few readily available sources of information concerning Simpson’s life. I have very little new information to add. The basic facts are as follows:

Simpson was born on November 10, 1845 in Platte County, Missouri and came to Oregon at six months of age with his parents Benjamin and Nancy (Cooper) Simpson. After residing several years in Oregon City the family moved to Polk County near the Grand Ronde Indian reservation.

At age sixteen Simpson enrolled at Willamette University, and after his 1865 graduation he began the study of law. He passed the law exam the following year, and was admitted to the bar in 1867. He afterward formed a partnership in Salem with fellow attorney J. Quinn Thornton, which lasted for only a few months. After two years of practicing law full time, Simpson decided to pursue a career as a newspaper editor, and in 1870 took charge of the Corvallis Gazette. One year later he moved to Salem and became editor of the Oregon Statesman, a newspaper for which he had served as editor four years earlier.

In June 1873, Simpson moved to San Francisco, after having secured an engagement to write the fourth and fifth books in Bancroft’s Pacific Coast series of readers. During this time he also contributed to the Overland Monthly.

After more than a year in San Francisco, Simpson returned to Oregon and for the next year assumed editorial duties on the Oregon State Journal at Eugene City, while editor Henry Kincaid was away in Washington, D. C.. Kincaid later wrote: “Sam was engaged, during the absence of the editor in Washington, to write editorials for the Journal. His writings were brilliant but irregular and could not be depended upon, as some weeks little or nothing was furnished.” (Powers, 291) The reason for this unreliability was simple: Simpson was an alcoholic. “The weeks without editorials were probably the weeks when he was not sober enough to write them,” speculated Powers, “for he takes front rank, with Burns and Poe, among the drinking poets.” (Powers, 292). As a result of his alcoholism, Simpson found it difficult to gain steady employment. Throughout his later years he drifted from one place to another, working on various newspapers at Astoria, Portland, and Ilwaco, Washington.

Simpson’s alcoholism also affected his personal life. He married a Willamette University classmate, Julia Humphrey, on July 30, 1868, and together they had two sons. After several years of marriage, however, the two were separated.

On June 12, 1899, an inebriated Simpson was walking outside the St. Charles Hotel in Portland when he slipped on the sidewalk and fell. The blow to his head caused irreparable damage, and he died two days later. He was interred at Lone Fir Cemetery in Portland. In 1927 a memorial to Simpson was erected at Lone Fir Cemetery by the Sons and Daughters of Oregon Pioneers.

Eleven years after Simpson’s death a collection of his poems, The Golden-Gated West, was published by his sister, Elanora “Nora” Simpson Burney, and his sons, Eugene and Claude.

“More than three-quarters of a century after his death, what is the measure of Simpson’s poetry?” asked Oregon author Ralph Friedman in 1978. “Certainly, he was not of major rank; what might have been is beside the point. Frances Fuller Victor, that perceptive student of literature, was quite correct when she observed, before the birth of the twentieth century, that Simpson ‘had written some of the finest lyrics contributed to local literature, though his style is uneven.’ To her he was no more than a regional poet—and time did not prove her wrong.”(Friedman, 67)

The poems that follow were written at various times in Simpson’s career. The original date and publication source, where known, are given. Several have been taken from The Golden-Gated West, but it is presumed that most of the poems in this collection were previously published elsewhere.

The First Fall of the Snow

In misty silence, dim and gray,

The haggard world last evening lay.

There were no birds at vesper call,

No garlands on the western wall;

No crimson kisses of the light

To warm the falling fringe of night,

As lowering his shield, the sun

Withdrew at once, and day was done.

The pines in plumy phalanx stood,

Embattled monarchs of the wood;

The oak, with stript and knotted arm

Invoked the challenge of the storm;

And asps and alders, by the streams,

Were lost in lonesome summer dreams.

A moment thus, in dark tableau,

You read the spectral sign of woe,

And then beside the roseate hearth

Forgot it all in ease and mirth.

You saw the ruby sparkles bloom,

And fade again in ashen gloom,

As memories, within your heart,

Like flowers flashed and fell apart,—

And all the while, with muffled tread,

The winds foretold the change that sped.

Perhaps in wakeful mood, last night,

You heard a whisper, low and light —

The sound of wings that touched and passed

The vibrant panes of window glass —

The rustle of a robe that kissed

The roof as soft as trailing mist.

‘Twas then a flaky lustre fell

In starry woof of asphodel,

And gloss of diamond, foam of pearl,

Inwrought in many an airy whirl,—

As if, in hyacinthine bowers,

Some sweeter anthem shook the flowers,

Like petaled moonlight o’er the globe—

A gleaming, soft, and magic robe.

And so, at morn, you wake to see

Our earth a lovely mystery—

A bridal orb, a blossomed star,

Redeemed of every woe and scar;

And yet this saintly crown shall pass

In golden bloom and tasselled grass,

When all the rippled streams shall sing

The coronation of the Spring.

The Golden-Gated West (1910). The second half of this poem has been omitted here. This poem was written circa 1879 according to William W. Fidler.

Hood

White despot of the wild Cascades!

I greet thee as the twilight shades

Haunt the disheveled, broken wall

Where sheaves of sunlight burning yet

On frosty tower and minaret

Portray thee, reigning over all!

And gleaming like a silver tent

Above the fir-fringed battlement

Cold Jefferson is crowned with flame;

Fair as a group of fallen stars,

The Sisters, linked with sunset bars,

Pledge thee as Monarch yet again.

The blazing quiver of the storm

Has hung upon thy lonely form,—

Sheathing its ragged barbs of fire,

When night has crushed its tempest wings

Against thy granite anchorings:

I read no record of their ire.

The centuries which o’er thee tramp,

Like spectres to their shadow-camp,

Beneath thee neither scar nor stain;

The gliding dimples of the sea,

The stars’ sweet-eyed eternity,

Do not a lovelier youth maintain!

And misty flashes of the morn

Are first upon thy shoulders born

When all the world is dark below;

And sunset’s last and lovely ray—

Dropped by the weary hand of Day—

Wreathes thy pale brow with ling’ring glow.

Thus Memory and Hope are wrought

Triumphant as the sculptor’s thought

When syllabled in marble speech;

And God-ward like a prophet’s prayer

Thou scalest the heaven’s windy stair

The quiet of the spheres to teach.

And what an empire! rough and shorn,

By old disorders ploughed and torn,

Sun-ward the mighty realms are spread;

In broidery of wood and mead,

Willamette’s green mosaics lead

Down where the rushing breakers tread.

Lodged in thy helmet’s icy clasp

The star of conquest rests at last,—

Never to lead the bold again;

Its rays like spears of silver laid

Across the grave, but newly made—

The Pioneer’s, in sea-side glen.

An iron arm with gleaming coil

Has won a wilderness for Toil!

The traffic of the seas are wed;

The morning of a brighter age

Than ever lit historic page

Lifts in the west its golden head!

With mutterings of doubt and fear,

And dark with battle long and drear,

The Pagan spirit of the past

Stalks through the silence and the night

That deepen with the ages’ flight—

Conscious of God and Truth at last!

The Desert hungers for the Sphinx,

Its tawny ocean swells and sinks

About her and the Pyramids;

The Simoom’s ghostly wings of sand

Will surely shroud them as they stand,

And seal those sad and weary lids;

And still a hand in chrystal mail

Here, flashing to the clouds, will hail

The tomb of Egypt’s cruel jest;

And where the sea-tides leap and shine

Along the New World’s border line,

Proclaim the Empire of the West!

Published in the State Rights Democrat (Albany, Ore.), January 14, 1870. This poem was significantly altered before it was published in The Golden-Gated West (1910). It is not known if these alterations were done by Simpson himself for a later publication of this poem, or if was altered by W. T. Burney, who edited the posthumous collection of Simpson’s poems, The Golden-Gated West. If Simpson’s other poems were altered in this fashion, it is no wonder Colonel R. A. Miller complained that “the over-editing of this book, by an ‘alleged literary expert’ of the East, had ‘ruined much of Sam Simpson’s work’ by presenting is in ‘this distorted form.’” (Powers, 300)

The Genii of the Flask

One dark and dreary winter’s day,

In times that long have passed away,

Portland, a scrawny village, stood

Knee-deep in pristine seas of mud,

With blackened stumps along the street

The frightened traveler to greet,

And, back of all, the firs, deep-massed

That moaned and whispered as he passed.

….The pale, low-wheeling, spectral sun

Its weary course had almost run,

But not a tint of sunset light

Signaled the town a fair “good-night.”

A heavy mist of mournful gray

Upon Willamette’s bosom lay,

And all was silence and despair

Save on the single thoroughfare

Where at some Bacchanalian fane

The glasses clinked a merry strain;

For it was New Year’s eve and all

The world was holding carnival.

Then up from that one gleam of life

Where men, inured to toil and strife,

Made merry on the gracious eve,

When all of cark and care take leave,

A pale and silent man was seen.

“I, too,” he said, “must e’en ask leave

To have one more my New Year’s eve,

And ‘Death’ shall be the toast I’ll drink

While hovering on the wild gulf’s brink.”

His eyes began to gleam and gloat,

And from his threadbare overcoat

He drew a heavy flask of liquor,

Which in the firelight seemed to flicker

With myriad strange and joyous lights,

The promise of untold delights,

Delights that fill the souls that come

Into the blessed Elysium.

He drank, drank deep, and sat him down

His solitary hearth beside,

And then upon his pallid face

You could with slight discernment trace

The purpose of the suicide

Who drank his lingering fears to drown.

Ah, well, sometimes we hardly blame

The actors in the deed of shame,

And thus his story soon is told;

He loved, as only such men love,

One whom he prized his soul above;

But poverty, with iron arm,

Thrust back affection overwarm,

And so at last, a hero bold,

He sought the West for needed gold.

‘Twas after wand’ring wild and drear

One smiling summer found him here;

And land be bought and settled down

To be the monarch of the town,

Which hardly was in embryo then,

The rugged camp of fearless men.

All was invested, but in vain

He watched for fortune’s shining wain

Through weary years, until the light

Of hope went out and all was night.

*……….*………. *………. *………. *……….*

He drank until he slept at last,

To make his own election sure.

*………. *………. *……… *………. *………. *

The years rolled on, the city grew,

Slowly but on foundation true,

and to our hero it is strange

Also should come with years a change?

Alack, it was all for the worse—

That magic flask became his curse.

It was his savior, so he thought,

And unto him the angel brought,

And so he worshipped it too well

And into hopeless ruin fell.

Again ‘tis happy New Year’s Eve

When men of cark and care take leave,

And one whom we have cause to know

Sits in the firelight’s fitful glow,

The very presence of despair,

From broken boots to tangled hair.

Hard drink has done it and his lands

Long since have gone to other hands;

But he has filled the flask once more

And has a dreary hope somehow

The angel of the shining brow

Will come as on the time before.

He sleeps at last, and wakes to see

A horror and a mystery;

‘Tis Orcus, now without a mask,

Arising from that fateful flask,

An awful shape—no words can paint

The terror of the fallen saint.

“I am your angel now,” he cries

“Your other friend is in the skies.”

Then with a mocking laugh and low

And in a swirl of azure flame

He sought the awful realms below

For which we have no fitting name.

The doomed one sleeps again, the day

Loos in upon him, cold and gray,

And yet he wakes not, all is o’er—

A prophet’s tongue could say no more.

Published in the Daily Journal (Salem, Ore.), July 11, 1899. This poem was evidently published several years earlier, but the original source is unknown. In reprinting this poem after Simpson’s death, the editor of the Daily Journal noted that this poem would be “familiar to old residents of Oregon but will be new to our visitors and many of the present day and generation.”

Falls of the Willamette

Here wheels the thunder-breathing steed,

As if in dread to stay and heed

….A grander pageant than his own,

Wild waters whirl in cresting spray,

Fair as the fragrant wreaths of May,

….And loud with laughter, song and moan.

Yonder embattled firs around,

Chant high above, in martial sound,

….The paeans of the marching years;

And here a dark, historic cliff,

Writ o’er with many a hieroglyph,

….Echoes and answers, leans and hears.

And lo! Within the surge and roar,

Scarfed with a rainbow evermore,

….The pallid priestess of the flood,

Swinging her censer to and fro,

As swift suns wheel and soft moons glow

….Aloof, through lapsing time has stood.

The tented and the tawny bands

Whose camp-smoke curled along these sands,

….And climbed and crowned the rocky shore,

To murmurless deep seas and pale

Have passed, with gray and slanting sail,

….Forgetful of the spear and oar.

So now beside this stormy gate,

Pilgrims of brighter visage wait,

….To rest in turn beneath the sod:—

Yet shall this melody be rolled

For aye, these voices manifold

….The echo of a changeless God!

The Golden-Gated West (1910)

At Linnton’s Shambles

[At Linnton, a village on the Willamette, is located an abattoir, where herds of Oregon cayuses are introduced through the canning route to the quartermasters of the armies of the world.]

With its blue seas afoam and its islands aglow

….And the continents loud with the clamor of life,

O, whither, O, whither, as dim cycles flow,

….Careereth the earth with its passion and strife?

As if lost in the night, to each other we call,

With lips moist with kisses or pallid with fear;

But out of the dark comes no answer at all,

….No solace from oracle, prophet or seer.

We are far from the highway; our landmarks are lost,

….And the stars reel above us in glimmering dance,

While our bacchanal torches, in high revel tossed,

….Portray that in darkness and doubt we advance;

Half God and half beast, we achieve what we dare,

….Defy every law in a rapture of sin—

Then away to our fanes with our hot bosoms bare,

….As if scourging and shrieking nepenthe might win!

Alas, it was yesterday only I saw

….How surely that people are drifting astray,

From dreams that were cherished, from loves that were law,

….And out o’er the battlements swarming away;

For at Linnton, down there where the shimmering tide

….Of the great river sweeps to the hoarse-calling sea,

Low singing, its murmur of anguish to hide,

….Are the red, reeking shambles the strange times decree.

A herd of wild horses, with streaming, tossed manes,

….In a grass field anear were disporting at will,

For the blood of Arabia throbbed in their veins,

….As they swept like a storm round the slope of the hill.

They were exiles from uplands beyond the Cascades,

….The pampas of sagebrush and bunchgrass their home,

Where only the stealthy coyote invades

….And the juniper scents the wild pastures they roam.

How glad were their gambols along the rich fields

….In the glory of sunlight that thrilled the grass seas,

For the beauty and ardor that sweet freedom yields

….Were theirs, as they raced with the sun and the breeze;

For the strain of the racers had moulded their limbs

….And arched their proud necks with a thunderous might

Which flamed in their nostrils, whose tremulous rims

….Expanded and quivered with royal delight.

O, that life of the plains! the jubilant rush

….Of the unbitted steeds on the deep-rooted turf,

Like the mad waves careering when storms wake the hush

….Of the slumbering ocean in billow and surf;

How they leaped in their pride, how their black banners streamed;

….For the world was still young in the original waste—

The dim mountain vistas with glamour bedreamed,

….And the wind and the waters exultant and chaste.

In time the young rev’lers must yield to the rein

….And their beauty and vigor inure to men’s needs,

For the splendor and dash of the life of the plain

….Is the glowing romance that preludes after-deeds.

But hark! from the tumult of cities is borne

….On the bland morning breezes, the rumble and roar

Of the steam-car and trolley—ah! let us mourn,

….For the dutiful day of the courser is o’er.

And hearken! With ominous “whisper and hum,”

….The gleaming road-eagles, the motor-cars, pass,

And the horse bows his head with disaster o’ercome,

….For his destiny’s over, alas and alas!

And now in this pasture at Linnton behold

….The herd that is doomed for the shambles hard by,

With October’s clear sunlight of mellowest gold

….On their handsome coats playing and kindling each eye.

They dreamed not of fate, how the cannibal man

….Would requite the devotion of glorious years—

Put sentiment, honor and worth in a “can,”

….With hardly the grace of reptilian tears.

O! shades of Bucephalus, splendid in war,

….Of the steeds that bore Sheridan into the fight,

And to love’s consummation the young Lochinvar,

….Are we smitten with madness, incurable blight?

Arise, Rozinante, bring Quixote again,

….Bold champion of maidens and scourger of wrong,

Let him ride down the crazy delusions of men

….And deliver the weak from the tyrannous strong.

O valor and beauty, and battle and love,

….Shall the ghouls have the horse and no hades have them,

Whom the stars, as they clash their gold lances above,

….And the winds and the waves in their anger condemn?

May Pegasus fiery, from Castaly’s stream,

….Drive hideous nightmares to rend their repose

Till their very hair stiffens in, struggles to scream,

….As the pale horse shall bear them to Stygian woes.

The Golden-Gated West (1910)

from Camp-Fires of the Pioneers

And now the last good-bye is said—

Good-bye! the living and the dead

In those sad words together speak,

And all your chosen ways are bleak!

And now the cracking lashes send

A thrill of action down the train,

Their brawny necks the oxen bend

And slowly move each covered wain;

And horsemen gallop down the line,

And wheel around the loosened kine

That straggle, lowing, on the plain,

And lift glad hands to babes that laugh,

And dash the buttercups like chaff.

Hurrah! the skies are jewel blue.

In plumes of green and braid of gold;

The Earth is wondrous to behold.

And hopes are light and hearts are true!

Hurrah! hurrah! the fair, the free,

The sudden sweep of ecstasy

That lifts the soul on wings of fire

When fears consume and doubts expire—

When the unfettered human thought

The oriflamme of hope has caught

And over sunset shore and seas,

Is trailing robes of mysteries.

*………. *………. *………. *……….*

A hundred nights, a hundred days!

Nor folded cloud, nor silken haze

Mellow the sun’s midsummer blaze.

Along the scorched and scorching plain,

All slowly drags the wasted train.

The dust starts up where e’re you tread,

Like angry ashes of the dead,

And veils you in its choking cloud

And wraps you in its awful shroud.

There is no longer any care.

To round the speech and speak men fair,

Or any staying sense of shame.

The hearts of all are sifted through,

The chaff is windowed from the grain,

And every where the false and true

Are stamped with signets deep and plain.

For some are silent, some are loud,

And urge like traits among the crowd.

And some are mild, and some are sharp

In word and deed, and snarl and carp,

And fret the camp with family broils.

And some with tempers sweet and bland.

Do seem to bear a magic wand,

That lightens all the daily toils,

As sandal wood in burning breaths,

Sweet odor in its curling wreathes.

And some go howling to their God,

And feign to kiss the heavy rod;

And some, maybe, with silent prayers,

Bend not in any griefs or cares,

But clench their teeth to do or die,

Without a whine, or curse, or cry.

And so the dust and grit and stain

Of travel wears into the grain;

And so the hearts and souls of men

Were darkly tried and tested then;

And so in happy after years,

When smiles have long outlived the tears,

If any friend should ask of you,

If such or such an one you knew?

I hear you answer, terse and grim,

“Ah, yes—I crossed the plains with him!”

And lo, a lurid phantom stands

To greet you in the lonely lands,

Among all lesser phantoms dight.

With spoils of death his meagre hands

Salute you as you pass and claim

The sacred fee that feeds his flame.

The march is now become a blight,

And wreck and ruin strew the path

As if you fled Jehovah’s wrath.

There are no birds to sing you joy;

You have no joy for birds to sing;

A hundred pangs of care annoy—

A thousand troubles fret and sting.

The desert mocks you all the while

With that dry shimmer of a smile.

That dazzles on a bleeding skull.

The bloom is withered on your cheek.

You slowly move and slowly speak,

And every eye is dim and dull.

Alas, it is a lonesome land

Of bitter sage and barren sand.

Under a bleak and friendless sky,

That never heard the robing sing,

Or kissed the lark’s exultant wing,

Nor breathed a rose’s fragrant sigh.

A weary land, alas! alas!

The shadows of the vultures pass

A spectral sign along your path;

The hungry wolf, with head askance,

Throws back at you a scowling glance

Of malice, hate and coward wrath;

A desert stretch, a reach of sand,

That crumbles at your lifted hand;

A dead, drear land, accursed, unknown,

In withered shroud asleep—alone—

Only the glimmering ghosts of seas

In broidery of flowers and trees

And rivers blue and cool, that seem

To ripple as in fevered dream.

Only to taunt your thirst and fly

The plains that glisten bleak and dry.

A hundred days, a hundred nights—

The goal is further than before,

And all the changing shades and light

Enwreath your souls with dreams no more.

A weary sun is overhead.

And fadded pampas round you spread,

A sere and sad eternity.

And if some grisly mountains rise

Like riven temples in the skies,

You turn in fear and pass them by.

And all are overworn and all

Unmask their hidden frailties then;

And some upon their Maker call

In fear that they have missed His ken.

And all are overworn; the flesh

Becomes a frail translucent mesh,

That will not mask the spirit now.

*………. *……… *………. *………. *

The ox lies gasping in the yoke

Beside the wagon that he drew,

Where the forsaken campfires smoke

To hopeless skies of tawny blue;

And while you’re straught you still must mark

The flight of life’s delusive spark—

The sombre pranks of grief that lie

So thick in human history.

And oh, so dark on this bleak page

Of drifting sand and dreary sage!

The sulky levels of the day;

The night with weird enchantment fills,

And mythic forests stretch away

Along the slopes of shadow hills,

And in the solemn stillness breaks

The wild wolf’s music of the plains,

As if a guardian spirit wakes

The dreary dead in that refrain

That swells and gathers like a wail,

Of woe from Plutus’ ebon pale,

Then sinks in pulseless calm again.

Published in the Pacific Monthly, July 1900; reprinted, with significant alterations, in The Golden-Gated West. “Camp-Fires of the Pioneers” is Simpson’s longest poem, and was written circa 1879. It was first published a year after Simpson’s death by William W. Fidler, from a first draft manuscript left by Simpson. Fidler explains: “The poem, as now presented to the public, lacks the final polish and finish of the author, as it was from the first rough draft that these fragments, after considerable pains and difficulty, were transcribed. The poet’s habit usually was to block out a poem in the rough, and then immediately prepare a perfected copy for publication. The improved version of this poem went with the volume he had hoped to have published. But that volume, in keeping with the run of bad luck that seemed to keep the author in continuous companionship, failed to get into print…As has already been intimated, the copy from which these fragments are taken was incomplete: it was written with pencil on both sides of the paper and no care taken to number the pages. In many places the lines are obscure and difficult to decipher. Where such was the case I have been forced to take some liberties with the verse, but always to the detriment of the poem. It would be bold assumption to pretend to improve on the finished versification of such a painstaking writer. Hence I have tried to follow copy in all instances where it was legible. The attempt to arrange the pages in their intended order of natural sequence has not been devoid of embarrassing difficulties, and complete success is far from being claimed. But the reader, I am sure, will pardon a few mistakes in this respect, in view of the wholesome feast of song herewith submitted.”

The Wreck of “The Wright”

The sun has set, and all alone

….The steamer battles with the sea;

Her plume of smoke is backward blown,

Beneath her prow, with bodeful moan,

….The conquering wave bends sullenly.

And, chill and drear, a shadow creeps

Along the wild and misty deeps

….That roll to windward and a-lee.

With maniac laughter, deep and low,

….The hungry caverns mock her way;

A pallid sea-bird, wheeling slow,

Shrieks to his mother-sea, below

….The hopeless flight of human prey;

And o’er the waste of water broods

The dreariest of Nature’s moods,

….Bereft of all save bleak dismay.

A sudden blenching strikes the sea

….To windward, and the fearful twang

Of Neptune’s trident hums a glee

Of might, and wrath, and agony,

….Far where the breakers boom and clang:

Like flying shrouds from rifled graves,

The pallid foam drifts on the waves,

….Whence ocean’s slumbering furies sprang.

Into the jeweled arms of night

….The mad storm leaps, his vap’ry hair

Drifts o’er her queenly breast bedight,

And quenches all its gemmy light;

….And down the corridors of air,

’Mong tapestries of cloud, the moon

Flits by with white, scared face, and soon

….Night and the storm hold empire there!

The stricken billows leap away

….With trampling thunders in the gale,

And straggering blindly to the fray,

The strong ship starts each bolt and stay;

….Her cordage shrieks, and with a wail

She plunges downward in the gloom

Of roaring gorges, hoarse with doom,

….And none alive may tell the tale.

What thoughts there came of home and friends,

….What prayers were said, what kisses thrown,

Were lost upon the wind, that lends

Its borrowed wealth no more, yet blends

….A sigh of trouble with the moan

That sadly haunts the restless waves—

Forever rolling o’er the caves

….Where richer things than pearls are strewn.

They sailed one day, and came—no more!

….All else is wrapt in mystery;

The surges kneel upon the shore,

And tell their sorrows o’er and o’er;

….And still above the northern sea,

A pensive spirit, pale and slow,

The gray gull, wheeling to and for,

….Keeps watch and ward eternally.

Published in The Pacific Coast Fifth Reader (1875); reprinted Oregon Native Son, September 1899; and The Golden-Gated West (1910). The steamer George S. Wright disappeared while sailing from Alaska to Portland, Oregon in January 1873. The mystery of what happened to the Wright has never been solved, although the steamer was presumed wrecked at sea, with no known survivors.

Biographical sources:

John B. Horner, Oregon Literature (Portland, Ore.: The J.K. Gill Co., 1902), 61-78; Alfred Powers, History of Oregon Literature (Portland, Ore.: Metropolitan Press, 1935), 289-304; Ralph Friedman, Tracking Down Oregon (Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Printers. Ltd., 1978), 58-70; Samuel Leonidas Simpson, The Gold-Gated West—Songs and Poems (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co., 1910); “From Oregon,” Springfield (Mass) Republican, February 23, 1867, 3; “New Law Firm,” State Rights Democrat (Albany, Ore.), December 28, 1867, 3; “Oregon,” Morning Oregonian, March 6, 1871, 2; “Gone to a Wider Field,” State Rights Democrat, June 20, 1873, 3; Oregon State Journal (Eugene), November 7, 1874, 3; Oregon State Journal (Eugene), April 3, 1875, 3; “An Oregon Journalist,” Oregon Statesman (Salem, Ore.), June 15, 1899, 1; “Sam L. Simpson’s Poems,” Daily Journal (Salem, Ore.), July 11, 1899, n. p.; Morning Oregonian, July 18, 1899, 4; W. W. Fidler, “Camp-Fires of the Pioneers: Fragments of an Oregon Aeneid,” Pacific Monthly, 4, no. 3 (July 1900): 109-113; W. W. Fidler, “Personal Reminiscences of Western Poets,” Bonville’s Western Monthly, 4, no. 1 (July 1909): 20-26.

Samuel Leonidas Simpson, the “Burns of Oregon,” is widely regarded as nineteenth century Oregon’s most beloved poet. A prolific writer whose poems and stories were published throughout the Pacific Northwest, Simpson is remembered today for only one poem, “Beautiful Willamette,” written when he was twenty-two years old. At the height of his fame, however, Simpson’s various talents were praised extensively by an adulating press. The following editorial from the Oregon State Journal, Eugene, is but one example: “Some of our contemporaries express the opinion, in which we freely concur, that Sam L. Simpson is the most brilliant literary genius in Oregon.” (November 7, 1874) Even after Simpson’s death, the adulation continued. One month after his passing, the editor of the Salem Daily Journal remarked: “[Simpson] will stand in literature as the greatest writer our state has produced.” (July 11, 1899) The editor of the Oregonian was even more blunt: “The death of Sam L. Simpson leaves an absolute blank in respect of the fact that we have among us no poet of merit or reputation.” (July 18, 1899) This pronouncement was made in spite of the fact that at the time, several prominent Oregon poets were still living, including Joaquin Miller, Belle W. Cooke, Frances Fuller Victor, and Ella Higginson.

Samuel Leonidas Simpson, the “Burns of Oregon,” is widely regarded as nineteenth century Oregon’s most beloved poet. A prolific writer whose poems and stories were published throughout the Pacific Northwest, Simpson is remembered today for only one poem, “Beautiful Willamette,” written when he was twenty-two years old. At the height of his fame, however, Simpson’s various talents were praised extensively by an adulating press. The following editorial from the Oregon State Journal, Eugene, is but one example: “Some of our contemporaries express the opinion, in which we freely concur, that Sam L. Simpson is the most brilliant literary genius in Oregon.” (November 7, 1874) Even after Simpson’s death, the adulation continued. One month after his passing, the editor of the Salem Daily Journal remarked: “[Simpson] will stand in literature as the greatest writer our state has produced.” (July 11, 1899) The editor of the Oregonian was even more blunt: “The death of Sam L. Simpson leaves an absolute blank in respect of the fact that we have among us no poet of merit or reputation.” (July 18, 1899) This pronouncement was made in spite of the fact that at the time, several prominent Oregon poets were still living, including Joaquin Miller, Belle W. Cooke, Frances Fuller Victor, and Ella Higginson.

practicing law in Canyon City, and was well-acquainted with both Joaquin and Minnie. “His wife’s name was Minnie Myrtle and I remember she used to write some excellent poetry,” he told Fred Lockley of the Oregon journal. “Heine used to come around once in a while or, rather, twice in a while and that was pretty often, to read poems to us, claiming that he was the author of them. I remember one that struck me particularly was a poem called “Gettysburg.” We talked it over among ourselves and decided that Miller was something of a fraud and was palming off his wife’s poetry as his own. However, as he continued to turn out poetry after his wife left him we came to the conclusion that the work was probably his own.” (Lockley)

practicing law in Canyon City, and was well-acquainted with both Joaquin and Minnie. “His wife’s name was Minnie Myrtle and I remember she used to write some excellent poetry,” he told Fred Lockley of the Oregon journal. “Heine used to come around once in a while or, rather, twice in a while and that was pretty often, to read poems to us, claiming that he was the author of them. I remember one that struck me particularly was a poem called “Gettysburg.” We talked it over among ourselves and decided that Miller was something of a fraud and was palming off his wife’s poetry as his own. However, as he continued to turn out poetry after his wife left him we came to the conclusion that the work was probably his own.” (Lockley) Ina Coolbrith, California’s first poet laureate, was known variously as “Sappho of the west” and the “Sweet Singer of California.” She was perhaps California’s best-known nineteenth-century poet, but her poems have been largely forgotten.

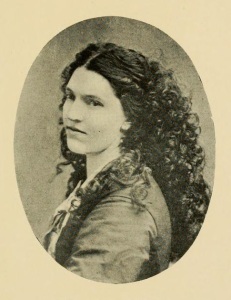

Ina Coolbrith, California’s first poet laureate, was known variously as “Sappho of the west” and the “Sweet Singer of California.” She was perhaps California’s best-known nineteenth-century poet, but her poems have been largely forgotten.

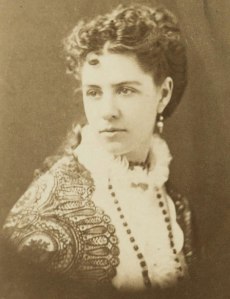

Eliza R. Snow is recognized today as one of the leading women in the early Mormon Church. In addition to serving as the second president of the Relief Society, she helped organize the children’s Primary Association and the Young Ladies Mutual Improvement Association, but she is perhaps best known as “Zion’s Poetess.” As a poet she employed a wide variety of poetic forms and meters, but it is her hymns for which she is remembered. The vast majority of her poetical works, however, are largely unknown.

Eliza R. Snow is recognized today as one of the leading women in the early Mormon Church. In addition to serving as the second president of the Relief Society, she helped organize the children’s Primary Association and the Young Ladies Mutual Improvement Association, but she is perhaps best known as “Zion’s Poetess.” As a poet she employed a wide variety of poetic forms and meters, but it is her hymns for which she is remembered. The vast majority of her poetical works, however, are largely unknown.

You must be logged in to post a comment.